CARLA ADAMS, TROY- ANTHONY BAYLIS, CHRISTINE DEAN, CHANTAL FRASER, KATE JUST, MUMU MIKE WILLIAMS, CLAUDIA NICHOLSON, RAQUEL ORMELLA, MARLENE RUBENTJA & PAUL YORE.

’CAN’T TOUCH THIS’

CURATED BY MIRIAM KELLY

31 AUGUST – 30 SEPTEMBER, 2017

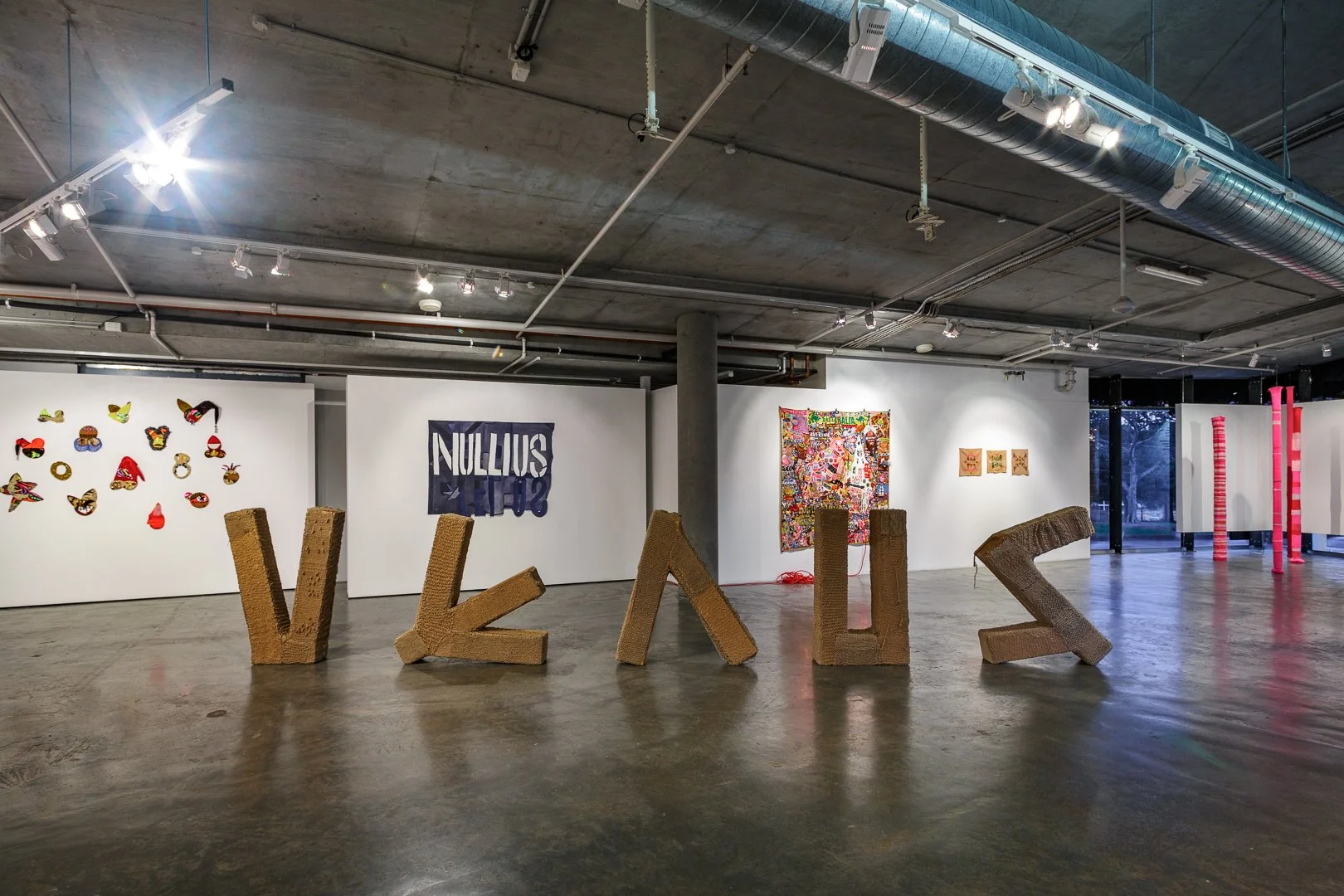

Can’t touch this, 2017, Installation shot. Photography by Document Photography.

ID: In the forefront, there is a large cardboard block letters spelling out ‘VEAUS’ in Roman lettering. In the back, there is a series of masks across the left hand side, with a poster in the middle that is dark blue and has white text stating ‘NULLIUS’ on it. To the back right hand corner, there is a brightly coloured collaged textiles piece that is hung, with red string sitting at the bottom of it, with neutral brown small posters to the far right.

EXHIBITION STATEMENT

The title Can’t Touch This started out as a nod to 1990’s pop culture and a nerdy curatorial joke about the desire to touch artworks, in particular those made from textiles, in defiance of gallery signage. It is like there is a special set of exemptions in our minds if an artwork looks soft, plush and familiar, maybe a little warm…

Our relationship to cloth is unlike any other medium in artistic practice, experienced primarily through its relationship to our bodies. Yet, because of this proximity, it is a medium that in many ways flies under the radar of our perception. Academic Maxine Bristow has described textiles as bearing witness through their proximity to our lives, being able to provide a “convincing testimony, not because they are evident and physically constrain or enable, but often precisely because we do not see them.”

Can’t touch this, 2017, Installation shot. Photography by Document Photography.

ID: In the middle of the page, there is a fabric work, that is hung on a wooden pole. The work displays Indigenous storytelling, with watering hole imagery and Indigenous language written around the drawings.

What drew me to so many of the works in Can’t Touch This is simply the act of making textiles visible. What does this do to our sensorial understanding of the material, and as a result the way we draw meaning from the work? In fact, this show began as a consideration of how, despite all that has changed in the past 33 years since Rozika Parker wrote The Subversive Stitch (1984), textiles still act as a mechanism in the visual arts to consider issues relating to marginalisation, gender, identity or Australia’s problematic political histories. Indeed, internationally we have seen a renaissance over the past five years of textiles in practices of artists who have long worked with the medium, alongside those for whom it is one of many avenues for expression.

Considered as a singular term, ‘textiles’ refers to all manner of material objects, from clothing, craft, bed linen, flags, towels and blankets; made with techniques of production such as knitting, weaving, rug making or embroidery. Each form that textiles take, and each context in which they appear hold layered associations, many serve in the social and political construction of class, culture, gender and identity more broadly. As an artistic medium, the ground-work laid in the latter half of the twentieth century with feminist subversions of the gendered and domestic (private vs public) associations of cloth, adds to this wealth of potential meanings that the material carries, that we as viewers bring to an object.

Can’t touch this, 2017, Installation shot. Photography by Document Photography.

ID: In the gallery on the right, there is a series of pink paintings that are placed along the wall, they are textured and look like there is fabric embedded into the painting. Next to it on the left is a fabric work, that is hung on a wooden pole. The work displays Indigenous storytelling, with watering hole imagery and Indigenous language written around the drawings. In the middle of the room, there are cardboard-like abstract structures, with fabric works behind them depicting portraitures of people. In the far left corner, there are some dolls sitting on white shelves, with bright pink cylindrical sculptures standing next to them.

While there are multifarious entry points into each work in this show, they were loosely brought together with within two broad approaches to cloth: use and labour. The use, or more accurately re-use, of cloth that has lived on or alongside us holds an extraordinary potency. Christine Dean Chantal Fraser and Raquel Ormella drew on found, gifted or inherited clothing. Academic Peter Stallybrass has written of the power of old clothes, and the shapes of body they hold with reference to “cloth is a kind of memory”. While Stallybrass’ text was rooted in loss of a loved one, Christine Dean’s works with men’s garments were characterised by a sense of celebration and revelation. Titled ‘Gender Euphoria’, Dean revisited the aesthetic of her pink monochromes (originally begun in the 1990s as an expression of “aching gender dysphoria”), reframing these cut up clothes, but saturating them in a largely gendered colour marks the first major body of work completed after her own gender transition from male to female.

Chantal Fraser began working with cloth after saving a large number of her father’s discarded ‘aloha’ shirts. In this ongoing body of work #traditionalblurredlines, Fraser now creates adornments with patchworks of an array of garments, fabrics and other materials inherited, gifted and found. Part critique of the wrongs of cultural appropriation in fashion and art Fraser’s works also illustrated a desire to formulate alternate forms of personal protection for positive pathways through the world.

I have always been obsessed with the potency of worn cloth for the expression of labour, so eloquently conveyed in the fading and wear of indigo dyed garments. Raquel Ormella’s Workers Blues #3, spoke to this in an incredibly nuanced and powerful way. Cutting and layering the language of Australian colonial expansion from these shirts, Ormella alludes to the role of political bannersand reflects on the problematic slipperiness of history and language.

Can’t touch this, 2017, Installation shot. Photography by Document Photography.

ID: There is a brightly collaged fabric work to the left of the image, with various amounts of Australian and Indigenous Australian iconographies sewn into it. There is a bright red string that has been sewn in and bunched up on the bottom of the wall. To the right, there is three small neutral brown coloured fabrics with Indigenous storytelling drawings on each one.

Mumu Mike Williams subverted the language printed on canvas Australia Post mail bags to co-opt them into statements in Pitjatjantjara about Aboriginal sovereignty. A warning that “theft or misuse of this bag is a criminal offence” was depicted on the side of these well-worn satchels that have traversed the nation. Yet, under the same laws governing these bags, the Commonwealth does not afford the same protection against theft or misuse of the lands and cultural heritage of the Mimili community, among others, against mining and other forms of contemporary colonial expansion.

In a comparatively brash and intentionally chaotic voice, non-Indigenous artist Paul Yore also demanded conversations about Australia’s past and present. Manipulating found fabrics and collected materials from all manner of contexts, Yore created images of excess that act as beguiling and disturbing mirrors of an saturated, hollow political slogan mongering world in which, as Yore notes “shock and awe” and spectacle have become the norm. In contrast with the cacophony of imagery, Yore’s works involve finely detailed, labor intensive processes, which acted as meditative time for the artist to both escape and reflect on the nature of what is being conveyed.

Similarly, Carla Adams conceptually engaged with a labour intensive process in wrangling semi industrial materials, creating her portraits of men. This offered time-based reflection on each subject. Considering the role of language in relation to gendered power, these were portraits of men that she had engaged with via Tinder. Each work is titled after the language of threat and physical violation that can occur within the disembodied experience of internet relations.

Kate Just and Troy-Anthony Baylis engaged with textile processes that reference the labour of their production to speak about the politics of the body. Baylis’ series of pink sculptures refers to the forms of Aboriginal memorial poles. Rendered in a medium associated with protection, care and warmth for the body, these poles were designed to celebrate and mourn the bodies of queer Aboriginal predecessors whose identities have been suppressed from or written out of both settler and Aboriginal histories.

Can’t touch this, 2017, Installation shot. Photography by Document Photography.

ID: To the left, there is three small neutral brown coloured fabrics with Indigenous storytelling drawings on each one. In the middle, there are five tall cylindrical bright pink sculptures that are places into a circle like format. On the far right, there are two dolls sitting on a white shelf, facing each other.

With VENUS Kate Just has sought out a means of re-examining historical mis/representations, specifically the Venus of Willendorf from a feminist perspective. Completed while on residency in Krems, Austria (near where the sculpture was originally found), Just collaborated with fifty five other knitters, working in public spaces to create the components of the cloth to cover the large scale letters. Here, Just considered the role of language in our shaping of constructions of history and power.

Claudia Nicholson’s embroideries were interesting examples of her approach to the material histories and their meanings. Nicholson has noted she looks for the potential to connect to her heritage “by incorporating established modes of artisanal practices from Central and South America and cultural representations found in popular culture.” These works were made with techniques of dying and stitching learned from a highly skilled artisan while on residency in Peru. Intentionally avoiding replication of the artisans practice, these intimate, napkin sized works explored the complexity of cultural identities, stitching Australian flag bikinis, Incan ceramic motifs gleaned from museum displays, and rare Amazonian pink dolphins that symbolise myths created to explain the offspring of Spanish colonisers in Colombia.

Marlene Rubuntja’s soft sculptures are portraits of three women from Larapinta Valley Town Camp who stitch with her at the Yarrenyty Arltere Art Centre. The works are made from old woolen blankets sourced from donations and op-shops. Dyed with local and found materials such as rust and leaves, Rubuntja adorned these blanket forms with an exquisite array of colorful yarn, this process, located within the art centre also marks the passing of time spent in conversation with fellow artists. The resulting work reflected the broader experiences of Rubuntja’s life in Larapinta Valley and narratives of self-care and community.

The artists in Can’t Touch This capitalised on an array of embedded and embodied meanings carried within used cloth and hand-made textile processes. Their works drew us in through our sensory understanding of this medium to convey their personal and political concerns in a uniquely engaging, albeit at times confronting way.

Sorry, you still can’t touch this.

Miriam Kelly, 2017